Zinc oxide has been used for decades as one of the most effective tools to prevent post-weaning diarrhea in piglets. Its efficacy is well recognized in the field, yet its mode of action remains complex and often oversimplified. Zinc oxide is frequently described as a simple antibacterial agent, but this view does not reflect the multiplicity of biological and physicochemical mechanisms involved. In reality, zinc oxide acts through several complementary pathways that depend on gut physiology, microbial dynamics, and the intrinsic properties of the zinc oxide source itself.

Let’s review that together!!

To understand how zinc oxide works, it is essential to clarify the origin of pathogenic Escherichia coli. There are two main sources of contamination. The first is endogenous. E. coli strains are naturally present in the piglet gut, including in the jejunum, where they usually remain at low and controlled levels. After weaning, abrupt dietary changes, stress, immature immunity, and altered gut motility create favorable conditions for these resident bacteria to proliferate locally and express virulence factors.

The second source is exogenous. Feed can introduce E. coli into the digestive tract, and these bacteria may multiply in the stomach, particularly in young piglets. At weaning, gastric acid production is still limited, and this situation is often aggravated by high inclusion levels of buffering ingredients such as calcium carbonate. When gastric pH increases, the stomach loses part of its antibacterial barrier function, allowing more viable bacteria to reach the small intestine and increase infection pressure.

Zinc oxide acts at two complementary levels. The first level is upstream, in the stomach. Zinc oxide limits bacterial proliferation by reducing the survival of E. coli under acidic conditions. By lowering the number of viable bacteria exiting the stomach, zinc oxide reduces the continuous reseeding of the small intestine. This effect is particularly important in piglets with low gastric acidity. The second level of action is at the intestinal epithelium. Zinc oxide supports gut integrity through several complementary mechanisms. Zinc directly upregulates tight junction proteins such as occludin, claudins, and ZO-1, improving tight junction assembly and reducing paracellular permeability. In parallel, zinc promotes enterocyte proliferation and villus recovery after weaning stress, restoring absorptive capacity. Enterotoxins produced by E. coli activate cAMP- and cGMP-dependent pathways in enterocytes, leading to excessive chloride secretion and passive water loss into the intestinal lumen. Zinc interferes with these signaling cascades, reducing chloride secretion and limiting water efflux even in the presence of bacterial toxins. As a result, zinc oxide does not only reinforce the physical barrier of the intestine but also dampens the secretory response, making the epithelium less permissive to diarrhea despite the continued presence of bacteria in the lumen.

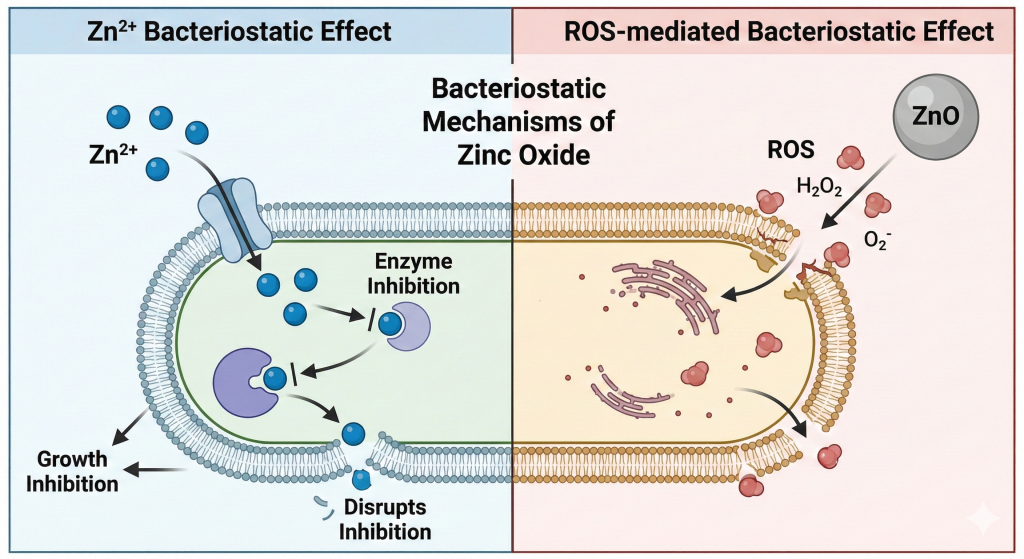

The antibacterial activity of zinc oxide is closely linked to the release of zinc ions, Zn²⁺, which can penetrate bacterial cells and disrupt enzymatic systems and metabolic functions. However, this effect requires relatively high local concentrations of Zn²⁺. Zinc ions alone are not sufficient to reproduce the antibacterial efficacy of zinc oxide, which explains why zinc sulfate fails to deliver comparable results at equal zinc levels. The key difference lies in dissolution kinetics. Zinc oxide dissolves slowly, creating a localized concentration gradient of Zn²⁺ around each zinc oxide crystal. Close to the particle surface,

Zn²⁺ concentrations can reach antibacterial levels, while they rapidly decrease with distance. This gradient is strongest in the stomach, where low pH favors partial dissolution, and weaker in the intestine, where pH is around 6.5.

In addition to Zn²⁺ release, zinc oxide exhibits a surface-mediated antibacterial activity through the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). In contact with water and oxygen, Zinc oxide is capable of producing reactive oxygen species such as superoxide radicals (O₂•⁻). This phenomenon is enhanced under acidic conditions, which explains why it is most active in the stomach and less effective in the intestine. These ROS are extremely short-lived and act only within a few nanometers from the zinc oxide particle. Their antibacterial action is strictly local and contact-dependent. ROS disrupt bacterial cell membranes, increasing membrane permeability and facilitating the penetration of Zn²⁺ ions into bacterial cells. The antibacterial efficacy of zinc oxide therefore results from a synergistic action between reactive oxygen species and Zn²⁺ ions generated at the particle surface, a mechanism that cannot be reproduced by soluble zinc sources.

In the intestine, zinc oxide particles do not remain uniformly dispersed in the lumen but become trapped within the mucus layer covering the epithelium. This localization allows zinc oxide to create localized zinc concentration gradients at the mucus–epithelium interface, which are critical for its biological efficacy.

The magnitude of this local zinc gradient directly determines the intestinal response. Higher and more sustained zinc concentrations in the mucus enhance epithelial barrier function by promoting tight junction stabilization and by modulating cAMP- and cGMP-dependent secretory pathways, thereby reducing chloride secretion and limiting water loss into the lumen.

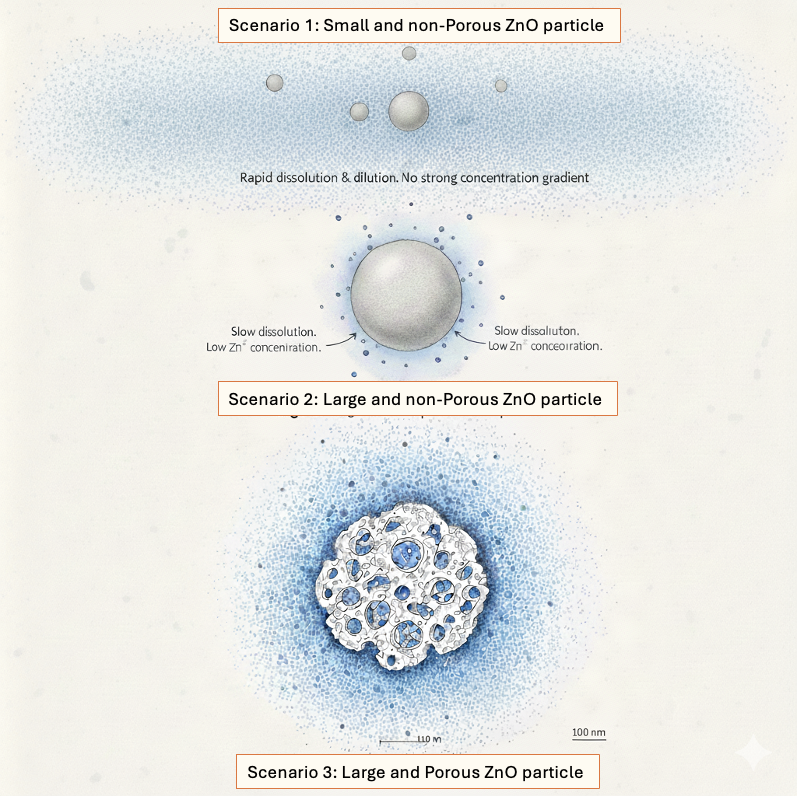

Regarding the ability to reach sufficient Zn²⁺ ions and ROS concentration gradients, both in the stomach for antibacterial activity or in the intestine for epithelium protection, not all zinc oxide sources behave in the same way. Four main types can be distinguished.

Scenario 1 = White Zinc Oxide made of small particle size and high surface area, often qualified as nano-zinc and commonly used in Asia, dissolves very rapidly in the acidic environment of the stomach. This rapid dissolution releases a large amount of Zn²⁺ ions over a short period of time, creating a brief zinc peak.

Because these ions are released without a solid zinc oxide particle acting as an anchor, they are quickly diluted throughout the stomach contents and lose their local concentration gradient. At the same time, free Zn²⁺ ions are rapidly chelated by phytates present in the feed. As most of the zinc oxide is already solubilized in the stomach, few or no solid zinc oxide crystals remain to reach the intestine. In practical terms, this source behaves very similarly to a soluble zinc salt such as zinc sulfate, providing zinc ions without sustained localization. As a consequence, it cannot effectively penetrate or persist in the intestinal mucus layer, limiting its ability to generate local high zinc gradients at the epithelium and to protect the intestinal barrier.

Scenario 2 = Large particle size and low surface area zinc oxide, black color, historically used in Americas, dissolves slowly and allows the formation of long-lasting zinc but low concentration gradients.

However, to compensate for low concentration gradients, high inclusion levels up to 3,000 ppm of zinc have traditionally been used. At such dosages, zinc oxide contributes to an increase in stomach pH due to its buffering capacity. In piglets with already limited gastric acid secretion, this rise in pH can reduce the stomach’s antibacterial barrier and partially counteract the benefits of zinc oxide.

Scenario 3 = Porous Zinc Oxide combining large particle size with high surface area, is designed to maximize persistence and reactivity along the digestive tract. This physical structure is optimal for creating high local concentration gradients of Zn²⁺ around the zinc oxide crystals, generating a microenvironment that is highly unfavorable for bacterial survival.

The combination of a solid mineral core and an extended reactive surface allows continuous zinc release directly at the particle interface, rather than a uniform dilution in the digesta.

In the stomach, this structure supports strong local antibacterial activity through sustained zinc gradients without relying on transient zinc peaks. In the intestine, where pH is higher and zinc oxide solubility is reduced, zinc oxide particles persist within the mucus layer and maintain localized Zn²⁺ gradients at the epithelium. These gradients are sufficient to activate epithelial barrier and secretion-control pathways, explaining the superior efficacy of high-porosity zinc oxide in reducing post-weaning diarrhea.

Coated zinc oxide is not a distinct zinc oxide structure but a technological modification applied to one of the three zinc oxide types described above. The coating is designed to prevent or strongly limit zinc oxide dissolution in the stomach. As a result, Zn²⁺ ions and ROS are mainly expressed in the intestine, where zinc oxide is released at a slower rate due to the higher pH. The efficacy of coated zinc oxide therefore depends not only on the coating technology itself, but also on the intrinsic physicochemical properties of the selected zinc oxide, including particle size and surface area, and should be considered as an intervention acting primarily at the intestinal level without the barrier effect on bacteria in the stomach.

In conclusion, the efficacy of zinc oxide cannot be predicted from zinc content alone. Particle size, surface area, dissolution kinetics, and coating technologies fundamentally determine its biological activity. Nutritionists should therefore avoid relying solely on manufacturer claims. Only rigorous physicochemical analyses, including particle size distribution and surface area measurements, allow an objective evaluation of zinc oxide sources. Even for coated products, these parameters remain critical to predict performance and design effective zinc strategies in piglet nutrition.

Ultimately, the goal is to create a highly concentrated gradient of Zn2+ and ROS. That local concentration highly depends on the zinc oxide structure.

David Serene

Nutrispices Director