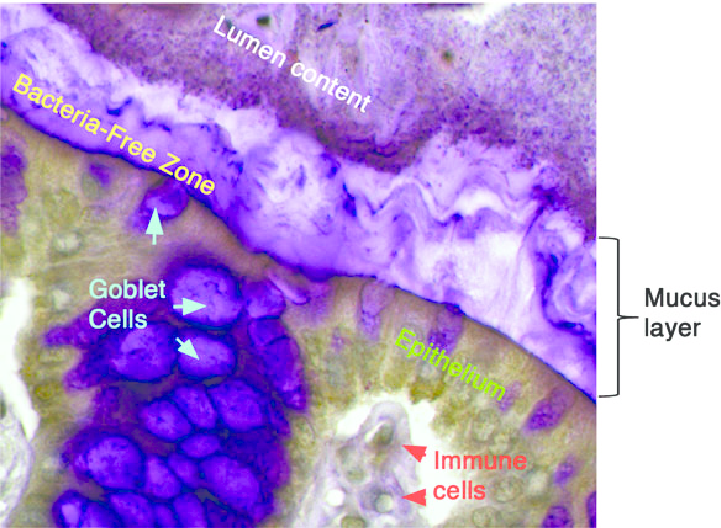

The intestinal tract of monogastric animals is a living interface constantly renewing and protecting itself. Along its wall, specialized goblet cells secrete mucus that forms a thin protective film over the epithelium. This mucus layer lubricates the passage of digesta, shields the intestinal cells from mechanical friction and pathogens, and provides a habitat for beneficial bacteria. It acts as the gut’s first line of defense while allowing nutrients to diffuse through to the absorptive cells.

But when it becomes excessive or overly viscous, mucus starts to interfere with normal digestive function. A thick mucus film creates a physical barrier between nutrients and the enterocytes, reducing the efficiency of absorption and increasing the apparent loss of amino acids and fat in the feces. It can also trap pathogenic bacteria and their toxins, allowing them to persist longer in the lumen instead of being cleared with the digesta. In young animals, excess mucus often leads to slower epithelial turnover, resulting in shorter villi and reduced digestive capacity. Another consequence is an increase in endogenous losses, because the animal must continuously produce and shed more mucus, which consumes energy and amino acids that would otherwise support growth. Over time, this creates a cycle where the gut remains protected but less functional, highlighting the importance of maintaining mucus at the right thickness rather than simply maximizing its production.

Maintaining the right thickness of the mucus layer is therefore essential to keep protection without compromising absorption. This is where insoluble fibers play a strategic role by helping regulate mucus turnover through gentle mechanical stimulation. It is called scraping.

Physical interaction between fibers and the intestinal wall

Insoluble fibers, particularly those with coarse particle size and rigid structure, exert a gentle mechanical friction on the intestinal mucosa during peristalsis. This friction detaches portions of the superficial mucus layer and removes some of the aged epithelial cells loosely attached to the villi. The process resembles a natural cleaning of the gut surface. Properly balanced, this scraping improves the renewal rate of the mucosa and maintains a thinner, fresher mucus layer, facilitating closer contact between nutrients and the absorptive cells.

Benefits of controlled scraping

1. Removal of excess mucus:

The intestinal wall is covered by a mucus layer rich in glycoproteins and bacteria. When mucus accumulates excessively, it can act as a diffusion barrier for amino acids and fatty acids. Moderate scraping reduces this thickness, improving the contact between digesta and enterocytes. This enhances nutrient digestibility and absorption efficiency.

2. Detachment of pathogenic bacteria:

Many enteropathogenic bacteria, such as E. coli or Clostridium perfringens, attach to epithelial cells through adhesion molecules embedded in the mucus. The mechanical action of fibers can dislodge these bacteria, reducing their residence time and limiting toxin production. This is particularly valuable in young piglets or broilers where the immune system is still maturing.

3. Stimulation of epithelial turnover:

The removal of aged or damaged epithelial cells triggers the proliferation of new enterocytes from the crypts. This rejuvenation accelerates mucosal recovery and sustains villus height, a key determinant of absorptive capacity. In this sense, fibers act as a physiological exfoliant, maintaining epithelial vitality.

When scraping becomes detrimental

Like many beneficial processes in nutrition, scraping must remain within physiological limits. When fibers are too coarse, too sharp, or supplied in excessive amounts, the mechanical stress on the mucosa increases. Instead of stimulating renewal, it may erode the villi tips and reduce the functional surface area. The result is nutrient leakage through damaged cells and reduced apparent digestibility, particularly of amino acids and lipids. Excessive abrasion can also trigger a defensive overproduction of mucus, resulting in an even thicker layer and reduced absorption. The consequences are slower growth, higher feed conversion ratio, and reduced gut integrity.

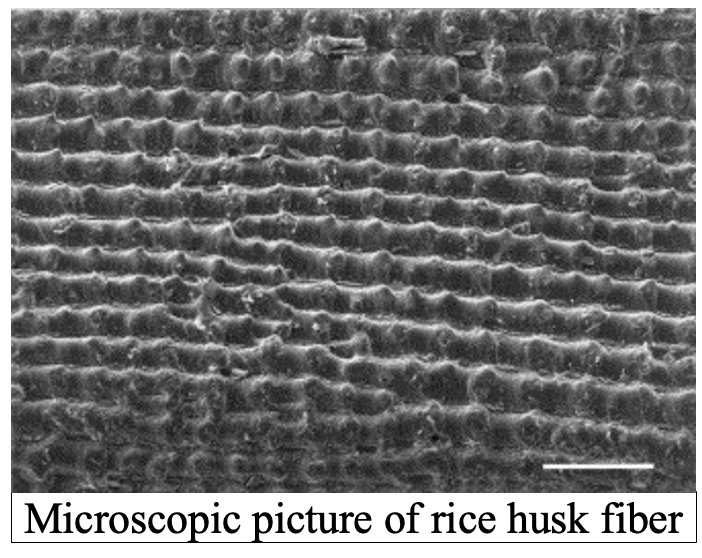

Certain raw plant residues are particularly aggressive and should be used with caution. The most abrasive fibers in feed are typically those with high rigidity, angular particle geometry, and significant silica content. The main ones are:

- Rice husk, which is considered the harshest because of its very high silica concentration and sharp hull fragments

- Barley and millet husks, which break into stiff splinters that can scratch the mucosa

- Unprocessed wheat straw or coarse wheat bran, where sclerenchyma tissues create needle-like particles when ground

- Sunflower hulls, especially in their raw form, as they are thick, brittle, and prone to forming sharp shards

- Sugarcane bagasse when only mechanically shredded, producing long and pointed fibers

- Palm kernel and coconut residues, which are extremely fibrous and remain harsh without extensive refinement

Optimizing the scraping effect

To gain the benefits without triggering adverse reactions, nutritionists should focus on three parameters: particle size, fiber inclusion level, and fiber source selection.

1. Particle size:

An optimal particle size between 300 and 600 microns is generally effective for stimulating peristalsis and mucus renewal without damaging villi. Below 200 microns, fibers lose their physical structure and act more as fermentable substrates than scrapers. Above 800 microns, they may irritate the mucosa and increase digesta transit too rapidly.

2. Source and structure:

To benefit from scraping without damaging the mucosa, nutritionists should favor processed fibers with low silica content rather than raw plant residues. These materials, such as purified lignocellulose, undergo mechanical and thermal treatment that standardizes particle size and surface geometry. During this process, the sharp edges of natural plant fragments are broken, producing rounded and uniform particles. Once hydrated, these particles form a soft and cohesive fibrous mass that moves smoothly along the intestinal wall.

This structure provides a gentle and controlled scraping, sufficient to remove excess mucus and stimulate epithelial renewal without causing erosion or villi breakage.

Conclusion

Scraping is a subtle and powerful mechanism through which dietary fibers sustain intestinal health in swine and poultry. When properly managed, it removes excess mucus, limits pathogen adhesion, and rejuvenates the intestinal lining, ultimately enhancing digestibility and growth performance. However, excessive abrasion can reverse these benefits, causing nutrient loss and mucosal damage. The art of formulation lies in selecting the right fiber source, maintaining an optimal particle size, and adjusting inclusion to achieve a gentle and beneficial cleaning rather than an aggressive abrasion of the gut surface. This balance is particularly critical in young piglets and broilers, where the intestinal mucosa is thinner and more sensitive to mechanical stress.

David Serene

Nutrispices Director